Do you live in an imaginary world?

Freya India offers a unified field theory for the digital lives chosen by way too many people

If you are of a certain age, you will remember when Johnny Carson was the king of late-night television. If you hear this name and draw a blank, then head to YouTube and prepare to laugh.

Now, if you know anything about the world of “Heeeeeerrrrrreeeee’s Johnny!” comedy, then you probably have a few favorite answers to this question: “How hot WAS it?”

The riff went like this. During his monologue, Carson would say something like, “Oh man, summer has really hit Los Angeles. It was HOT today.” At that point, the studio audience — knowing its role — would shout: “How hot was it?!?”

Carson would then offer the latest in thousands of responses to that question, such as:

* It was so hot that I saw a fire hydrant flagging down a dog.

* It was so hot that I caught Doc and the band snorting ice cubes.

* It was so hot that I saw a robin dipping his worm in Nestea.

You get the idea.

Now, what does this have to do with yet another must-read After Babel essay by Freya India? I am talking about the one that ran with this double-decker headline: “We Live In Imaginary Worlds — This is all one big hallucination.”

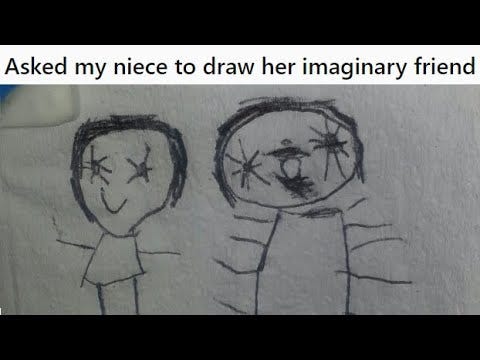

On one level, this is a short essay about children and people with imaginary friends. I couldn’t identify with that very much since, when I was a child, I didn’t have any imaginary friends. I had books and music. In high school, I did have an imaginary radio station consisting of cassette tapes full of great music, with me and my real friends offering introductions and chatter. But that’s another story, I guess.

India’s big idea, I guess, is that children now have imaginary friends that are created for them by software entrepreneurs and profit-hungry algorithms.

When these children grow up, they end up with adult versions of imaginary friends, lovers and maybe even pastors. This leads us to recent Rational Sheep offerings with headlines like “The Women with AI Boyfriends” and “OMG, this is way stranger than an AI boyfriend.”

But here is the theme in India’s essay that made me think of Johnny Carson and his riffs on the weather. She links the world of digital imaginary friends to — this is the theological “signal” that you can look up in a Bible concordance or commentary — the plague of loneliness in modern life. Here is the overture:

We are all aware by now that this is a lonely age. Friendships feel shallow and superficial. Local communities have deteriorated. The promise of constant connection turned out to be a cruel trap. A generation with access to billions of people say they feel lonelier than pensioners.

Since I was teenager, it seems like everyone has been selling a solution to Gen Z’s loneliness problem. One app after another to find new friends! Constant hashtags and campaigns to bring us together. For years I’ve been promised that some new invention will finally solve the problem (Does anyone really believe that an app will be “the antidote to America’s loneliness epidemic”?)

But I’ve noticed that, recently, the latest “solutions” have nothing to do with meeting in real life. They aren’t encouraging face-to-face friendships or trying to create new communities. They don’t even pretend anymore. At least friendship apps had the pretence of meeting up in person, even if it was always one more swipe or premium package away. Now these solutions have nothing to do with the real world. Now we are being invited into imaginary worlds.

This is where I heard the voice of Johnny Carson in my head, making jokes about something that’s actually very serious.

I heard this. “Oh man, there are lots of lonely people these days!”

All together now: “How lonely are they?!?”

That brings us back to India’s essay. People are SO LONELY that they are paying — with their time and their money — for …

This is long, but essential:

There are the imaginary boyfriends and girlfriends, of course. There are imaginary therapists, a “mental health ally” or “happiness buddy” we can chat with about our problems. And imaginary friends, like that AI necklace who is “always listening”, announced with the tagline: “introducing friend. not imaginary.”

There are even entirely imaginary worlds now. Metaverse platforms might “solve the loneliness epidemic”, apparently. VR headsets could end loneliness for seniors. But by far the most depressing invention I’ve seen lately is anew app called SocialAI, a “private social network where you receive millions of AI-generated comments offering feedback, advice & reflections on each post you make.” In other words, your own imaginary ‘X’, with infinite “simulated fictional characters”. You, alone, in a vast social network of AI bots.

Now we are raising children in imaginary worlds and at the same time killing their imagination. That’s the real cruelty about this. Kids today have their imaginary worlds generated for them. Instead of writing their own stories, they can put prompts into ChatGPT. Instead of creating their own fantasy worlds, they cangenerate them with a few clicks. I remember me and my friends spending hours after school writing our own songs, coming up with lyrics and drawing album covers—now we would justgenerate it with an AI song maker. Children are playing together less, replacing free play with screen time, and creativity scores among American children have been dropping since the 1990s. Part of that may be because children now depend on companies to be creative for them. Their imaginary worlds are designed by software engineers. Their imaginary friends are trying tosell them something. My imaginary world wasn’t trying to drag me anywhere, while algorithms now transport kids to darker and ever more extreme places.

This is why I’m skeptical of headlines I’ve seen over the years declaring that children have lost their imaginary friends. “Children have fewer invisible playmates than before,” we are warned. “Children too busy with their iPads to have an imaginary friend,” nursery workers say. I understand what they mean. But they haven’t really lost them. They just replaced them.

And the adults? More of the same, in some way. It doesn’t take long for the algorithm gods to spot our essential interests and passions (and the products that we search for the most).

The loneliness is real. So are the interests and passions. But it’s hard to share all of that with real people, right? After all, people are so, so busy today. (How busy ARE they?!?)

Brace yourself. Digital consumers can end up with …

Our inner worlds, which we can now scroll through. Where we can now live. This is all one big hallucination. … Adults also live in imaginary worlds. We now have adults who invest more time into their imaginary worlds and reputations than their real ones. Adults imagining they are “socializing” all day when they haven’t left the house. Adults editing their pictures, creating imaginary versions of the selves they pretend to be. Adults arguing with versions of people they have imagined in their heads. Adults ignoring their children to have fun with hallucinations.

Can you see why I want you to print out India’s essay and hand it to your priest, your pastor, your rabbi or some other analog person in your life who is supposed to be providing guidance on subjects of this kind?

We had better wrap this up. Here is India’s conclusion:

If someone is selling you a cure to loneliness that comes on a screen, is downloaded from an App Store, or invites you into an imaginary world, I suggest you decline. Keep your money. The only solution to loneliness is in each other. Reaching out to each other, approaching one another, and having the guts to say, God, I feel so lonely, do you? We can’t buy belonging. We can only build it, together.

The real world is waiting.

OK, I will ask: What will the algorithms offer us in the world to come?

The Nativity of Lord is a perfect antidote. Incarnational preaching is needed now more than ever.

You didn't mention AI Jesus?